We continue to grow our library of ready-made experiments with more classics. As always, you can import them straight to your dashboard and use it to collect data right away or first adapt them to your needs.

Many of you have asked us to add more survey-based templates of commonly used assessments. So in this batch we are adding two more standard assessment tools for Depression, Anxiety and Stress and a Need for Cognition test. As always, they come with automatic scoring, which makes it super easy for you to analyse results from assessments built in Testable.

Here are the five templates we added:

This very short 21-item questionnaire is a tool to briefly assess someone’s current emotional state. The scale dedicates 7 questions to each of the 3 dimensional conceptions of depression, anxiety and stress. As such, it is not recommended as a tool to classify as people suffering for any of the three related disorders and should not replace a facial clinical interview for making diagnoses.

in the Testable results file, you will find a column named “score”, which shows the aggregated score for each of the three segments, labeled D (Depression), A (Anxiety) and S (Stress). You can easily compare that score against the scoring table below.

The need for cognition is a stable personality trait that measures individuals’ tendency to engage in and enjoy effortful cognitive activity, Or in simpler terms, people’s willingness to think deeply.

There are various surveys with which you can measure this personality trait. This ready-made template encompasses the short, 6-item version. Items in this questionnaire are statements like “I would prefer complex to simple problems.” or “Thinking is not my idea of fun.” that need to be rated on a 5-point scale from “Extremely uncharacteristic” to “Extremely characteristic”. The scoring ignores any statements that are rated as “uncertain”. For details on interpreting the scores from this test you can check out this website.

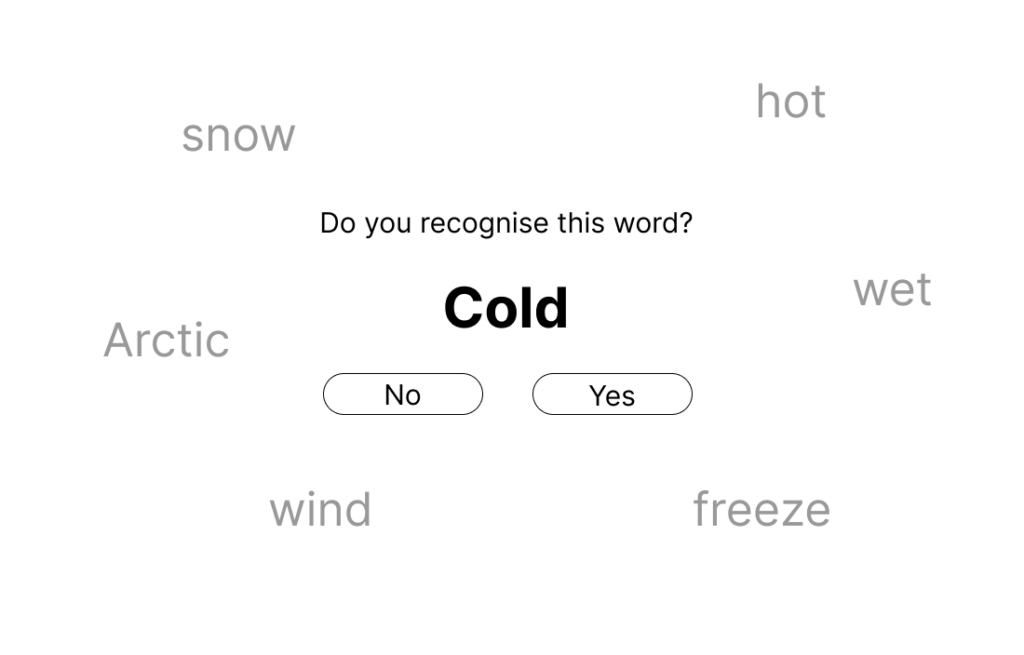

This is another classic memory experiment that every student comes across in their cognitive psychology class. It’s also a fun one to try on your friends, as it produces a surprising and reliable effect that tells us a lot about how our minds work.

In his test, participants need to memorise lists of 15 words as well as they can. In the second stage, they will decide if words from a new list were also present in the first or if they are novel. The twist: Many of the words in the learning phase are related to a semantic theme. For examples words like “snow, hot, ice, freeze, arctic” might all be part of one list. Importantly, the word that is related to all of the others (”cold”) is NOT present in the learning list. But during the recognition phase, participants will be asked if they recognise the word “cold”. This word is the “critical lure”, a semantic trap if you will, and we are curious to see if participants will fall for it.

We want to find out if participants will report that they have (falsely) seen this word during the learning phase more than for other words. If the answer is yes, then we have an impressive and simple demonstration of how false memories can be created under certain condition. Also, it is a vivid demonstration how neural activation spreads through our semantically organised brains.

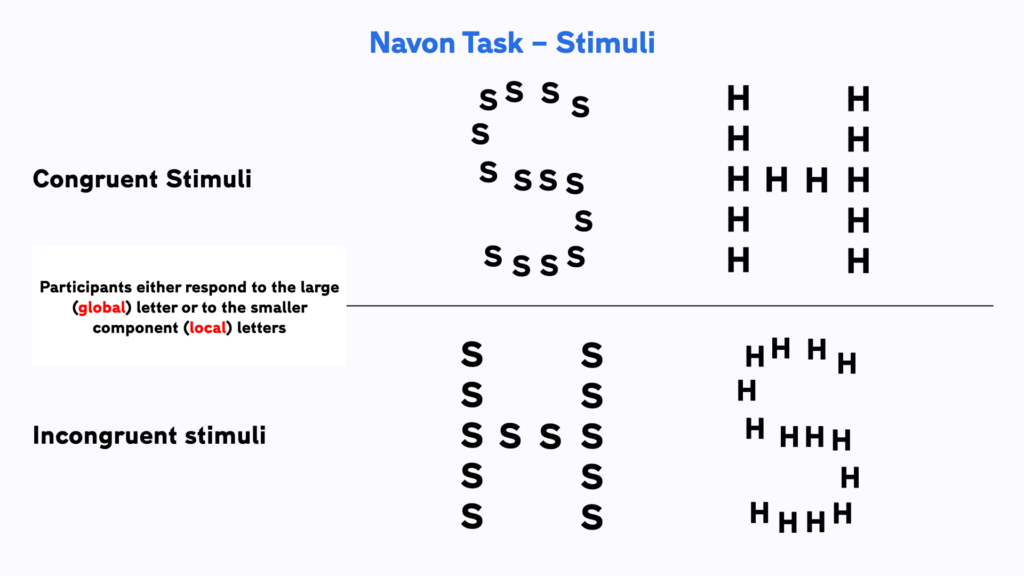

The Navon task is a true Psychology experiments classic. It’s a demonstration of the cognitive competition between “global” and “local” processing. It’s what we hint at when we are using the proverb “not seeing the forest for the trees” (in-depth experiment guide available soon).

In this simple experiment, participants see stimuli where large letters (H or S) are composed of many smaller letters which are either the same or different to the big letter. In one part of the experiment, participants need to pay attention to the big letter (”global” processing) and in the other part to the small letters that make it up (”local processing”). In other words, participants need to ignore either the small features or the big picture.

When the local and global letters do not match up, RT performance should drop during the interference caused by the conflicting perception. But this RT cost will be different between the “global” and the “local” conditions. Can you guess if we are better at ignoring the features or the big picture?

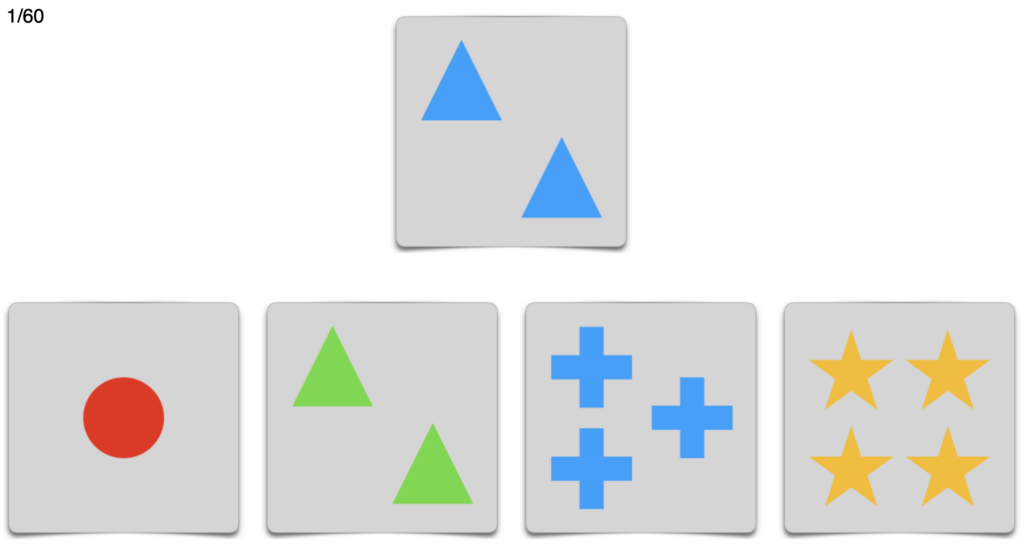

The Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (WCST) was initially developed by David Grant and Esta Berg in 1948. It was designed to measure the ability to flexibly adapt to changing reinforcement schedules. In other words: how fast can someone adapt to a change of rule, after a different rule has been previously learned.

In each trial of this task, participants need to sort one card to one of the four trials below. The cards have a number of features like colour, shape and number that can be used for sorting. The rules are not visible, so the participants need to find the rule (i.e. “color matters”) by trial and error, as they receive feedback after each trial. After some trials, the rule changes and participants need to adapt to the new rule, again using trial and error. We’re interested in how quickly the rules are learned, and how easily participants find it to detach from a formerly learned rule to adapt to a new one.

The WCST is routinely used as a measure of frontal lobe dysfunction, as the type of mental adaptability needed to succeed in this task is strongly linked to the healthy function of our frontal lobes.